Daily Excerpt: An afternoon's Dictation (Greenebaum) - Call to Interfaith, Chapter Three (Scripture)

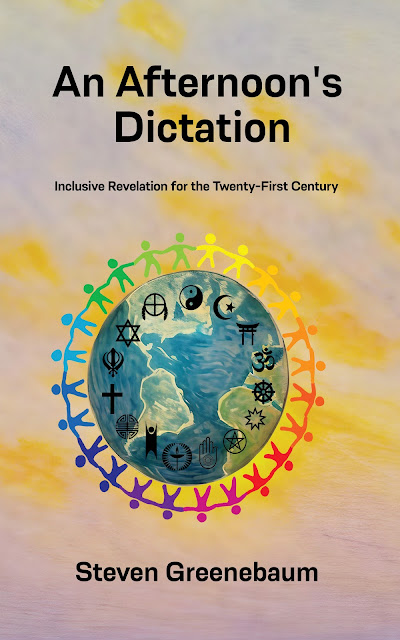

Today's book excerpt comes from An Afternoon's Dictation by Steven Greenebaum. This book has been in the Amazon top 100 among interfaith and ecumenical books on many occasions.

PART ONE: THE CALL TO INTERFAITH

CHAPTER THREE

Scripture has long fascinated me. Growing up Jewish, my

first experience with scripture was, of course, Hebrew scripture. Most

particularly, I was introduced to and schooled in the first five books of

Hebrew scripture, what we call Torah. Torah is considered particularly sacred

and important. And the study of Torah is considered a life-long task. As Rabbi

Tarfon put it some 2,000 years ago, we can never finish our study, but that

does not mean we can or should avoid it (“Pirke Avot” 2:16).

That approach to scripture calls to me. Consider what it

means that we are not called to memorize our sacred writings. Nor are we called

to read scripture once or twice, or even three times and then put it away. We

are called to study it. And as we won’t be studying scripture alone, it means

that we will discuss it and from time to time even argue about it, though amiably

one hopes. And we are called to keep revisiting it. The implication, for me, is

that scripture is to be considered a living, breathing document, not a text

frozen in time. How we look at scripture and interpret it will, then, change,

not only over the millennia of human history, but also over our own lifetimes

as our life-experiences change (in the Appendix, I share a recent example, a

new revelation that resulted in a reexamination and then reinterpretation of

the 23rd Psalm).

There is as well an intriguing question of what’s to be done

when scripture flat out contradicts itself? Say what? The first contradiction

that leapt out at me as a youth, and indeed seemed to grab me by my lapels and

say “Look!” was in the very first book of Torah: Genesis. According to Genesis

1:27, on the sixth day, God created male and female, both in God’s own image

and at the same time. But then, according to Genesis 2:7-23, it’s after

the seventh day that God created the first human. Adam and only Adam

was created from the dust of the ground. God then breathed life into him. Only

after creating the Garden of Eden did God think that Adam shouldn’t be alone.

So God created … not the first woman, but the beasts of the field and the fowl

of the air. It was then, only then, when this still wasn’t enough, that God,

seemingly as an afterthought, created Eve—not from the dust of the ground and

by breathing life into her as Adam was created but by causing Adam to go to

sleep and taking one of his ribs.

What infuriated me, even as a youth, was that it was this

second story that everyone knew and quoted. It was as if the first account

didn’t exist! That there were two stories was certainly intriguing, but for

some reason, that didn’t bother me as much. It seemed another good reason to

remember to study Torah, not merely glance at it and never look back, but that

we so completely adopted the story that made Eve’s creation an afterthought was

one more reminder of the cancer of patriarchy that I believed so plagued

Judaism (patriarchy has been a life-long “hot button” issue for me – for

context, see One Family: Indivisible).

Having two diametrically opposed stories of human creation

also taught me that however much scripture might begin as the word of God, we

have received that word through imperfect human hands. What I took from my

studies was that scripture could not and did not provide unmitigated,

unchangeable truth. This, it seemed to me, was what Rabbi Tarfon (and so many

others) had been talking about. Study Torah, and keep studying it. And don’t

just mindlessly study: think about it!

Another important reason for studying Torah came as I

contemplated two other crucial passages. The first was in Genesis (18:20-33).

God is angry at the sins of the people of Sodom and Gomorrah and plans to

obliterate them. Yet, Abraham doesn’t say, “Yes, Lord. Whatever you say, Lord. I

am your servant, Lord. I will do whatever you tell me to do.” No. Instead of

blind obedience, Abraham argues that it would be wrong to destroy everyone in

the cities if there might be good people as well. Abraham starts with 50, and

once God agrees to spare the cities if there are 50 righteous people, Abraham

keeps arguing until the number gets down to ten. Now, there aren’t ten, and God

destroys the cities. But Abraham arguing with God about justice? Wow! That’s

indeed a life-lesson!

The clincher came in Exodus (32:7-15). God and Moses are

having a nice chat atop Mount Sinai, where, among other things, Moses receives

the Decalogue (the Ten Commandments), but below them, hearing nothing from

Moses or God, the Children of Israel grow restless and fashion a golden calf to

worship. They are ready to forget God and worship a golden calf! God loses it

and is ready to wipe the Children of Israel off the face of the Earth—each and

every one of them! But like Abraham before him, Moses doesn’t say “Yes, Lord.

Whatever you say, Lord.” Instead, Moses argues that to lash out in anger and

obliterate a people would be wrong. It would not be just. Moses has the

courage, perhaps even the audacity, to tell God to repent. Again, that’s Moses

telling God to repent! And God does. Again, wow!

What to make of this? This is fundamental stuff, coming from

the Torah, the most sacred text of Jewish scripture. Do I personally believe that

Abraham and Moses actually got God to put aside irrational anger and a thirst

for violence? No, I don’t. But there it is, in scripture! If our scriptures are

the inerrant, immovable Word of God, it makes no sense, but if our scriptures

are not a never-changing rulebook and instead are a very human attempt to

interpret the Word of God, to be studied, pondered, discussed, and, from time

to time, even argued about, then it makes perfect sense.

What I took from these passages in Genesis and Exodus is a significantly

important lesson in not blindly following authority. I don’t believe in a God

who loses it one moment, only to be saved from destructive anger by human

interaction. What I see and am guided by is a lesson from God that no call

to injustice should be obeyed, regardless of where it comes from, even if we

think it comes from God. God is teaching us (as well as Abraham and Moses) that

it is justice that counts. I believe in a cosmic call to justice that was glad,

even relieved, that Abraham and Moses rose to take the “bait” and argued. Obey

the call of justice! That is an immensely important lesson. I fear it is a

lesson that humanity continues to struggle with to this very day.

“Now wait!” you may well say. At least, I hope you will.

This is just your interpretation; it’s just one person’s opinion. Yes, a

thousand times, yes!! This is precisely why we need to ponder scripture, not merely

read and quote it. Clearly, it seems to me that the very human people who in

antiquity wrote the scripture down believed in an angry and vengeful God. So,

thinking that God was angry and vengeful and had to be talked out of acting

angrily and without justice by both Moses and Abraham made sense to those

scribes, but it doesn’t make sense to me. I don’t believe in an angry and

vengeful God. I believe God, whoever and whatever God may be, is about justice

and love, not anger and vengeance. Which takes us again to an approach to scripture

of discussion and pondering, not blind obedience and quotation.

As a Jew, I look back at the history of Judaism, and it seems

clear that in its early days Judaism indeed embraced the idea of an angry and

vengeful God. Today, Judaism views God as a God of love and justice. So, did

God change? Personally, I don’t think so. I believe it is we who have changed,

and as we have changed, how we see the sacred (whether or not we use the word

God) has changed as well. When I was younger and into my 50s, I looked at this

primarily through the lens of Judaism. But then I received the revelations that

pointed me to Interfaith.

Many have

spoken for Me. They were righteous and they did carry My words. But I am not

human, and you are not God. Language can be a barrier between us as well as

yourselves that can be all but impossible to breach. Seek truth in the

commonality of religions—which are but the languages of speaking to Me. Worship

not the grammar.

After living with this and pondering it, it pointed me to

more than simply rethinking my approach to the “grammar” of our differing

traditions. The call was to seek truth not in what separates our spiritual

traditions but rather in what unites them. This is the heart and soul of

Interfaith: seeking truth in the commonality of our diverse religions.

We’ll go more deeply into that in the next chapter. For now,

what does it point us to in terms of how we deal with scripture? I have

consciously dealt above only with Hebrew Scripture. It is the scripture I grew

up with and the scripture of my heritage. At this point in my life, age 74, I

have read (in translation, of course) the scriptures of many spiritual

traditions. I have used the example of my own scripture, the one I am most familiar

with, but would invite the reader to ponder and examine the scriptures (sacred

writing if scripture becomes a limiting word) of their own spiritual tradition.

For me, our scripture is importantly influenced by the era,

culture, and life experience of the believers who received it and wrote it down.

Our scriptures, then, are guidebooks, not rulebooks. They are crucially

important guides for living a more meaningful life, and not repositories of immovable,

unchanging spiritual interpretations from hundreds, and for many of us,

thousands of years ago. Perhaps most important, all scripture, all scripture

is, at its most holy, a translation or, if you will, an interpretation of

sacred revelation. Even at its beginning, assuming that the beginning of our

holiest passages in scripture was indeed divinely inspired and began as

communication from God, it can only be what we imperfect humans have

interpreted that Word to be. And that interpretation can change. These

differences in interpretation are a major reason why virtually all of our

spiritual paths have branches. As but one example that most will be familiar

with, in Christianity there are the Catholic and Protestant branches. And there

are branches within those branches, all, in large part, from interpreting a

common scripture differently. Christianity is, of course, not alone. Judaism

has branches, Islam has branches, and so on. This is an important and complex

subject, and we’ll return to it later.

For now, what this means to me is that I feel called to

respect the sacred texts, the guidebooks of all my brothers and sisters, even

as I, being Jewish, cleave to as well as question the guidebooks of my own heritage,

all the while remembering that interpretations of these guidebooks can and will

vary. This includes the whole of Jewish scripture as well as the additions,

qualifications, and reinterpretations made over the centuries as our eras and

experiences have changed. This includes particularly but not solely the “Pirke

Avot,” the wisdom of the fathers, which houses the sacred writings of the rabbis

such as Hillel and Tarfon.

So, what truth is available to us by seeking the

commonalities of our diverse traditions? And how does this help us to answer

the call of Interfaith?

Book Description:

Indies Today runner-up

Firebird Book Awards honorable mention

Pacific Book Award finalist (runner-up)

American Legacy Book Awards finalist

For more posts about this book and its author, click HERE.

To purchase copies of any MSI Press book at 25% discount,

use code FF25 at MSI Press webstore.

Want to read an MSI Press book and not have to buy for it?

(1) Ask your local library to purchase and shelve it.

(2) Ask us for a review copy; we love to have our books reviewed.

VISIT OUR WEBSITE TO LEARN MORE ABOUT ALL OUR AUTHORS AND TITLES.

(recent releases, sales/discounts, awards, reviews, Amazon top 100 list, author advice, and more -- stay up to date)Check out recent issues.

Interested in publishing with MSI Press LLC?

Check out information on how to submit a proposal.

We help writers become award-winning published authors. One writer at a time. We are a family, not a factory. Do you have a future with us?Turned away by other publishers because you are a first-time author and/or do not have a strong platform yet? If you have a strong manuscript, San Juan Books, our hybrid publishing division, may be able to help.

Planning on self-publishing and don't know where to start? Our author au pair services will mentor you through the process.

Interested in receiving a free copy of this or any MSI Press LLC book in exchange for reviewing a current or forthcoming MSI Press LLC book? Contact editor@msipress.com.

Want an author-signed copy of this book? Purchase the book at 25% discount (use coupon code FF25) and concurrently send a written request to orders@msipress.com.Julia Aziz, signing her book, Lessons of Labor, at an event at Book People in Austin, Texas.

Want to communicate with one of our authors? You can! Find their contact information on our Authors' Pages.Steven Greenebaum, author of award-winning books, An Afternoon's Discussion and One Family: Indivisible, talking to a reader at Barnes & Noble in Gilroy, California.MSI Press is ranked among the top publishers in California.

Check out our rankings -- and more -- HERE.

Comments

Post a Comment